While I was living with my mom, she restricted what I ate to no end as typical Jamaican parents do. When we would go grocery shopping, I’d hop at the end of the cart, begging her to push me and, of course, she declined. I figured I would get my way by other means. She walked up and down the aisles looking for new spreads, marinades, or spices to add to her meals, and with what I imagined to be incredible stealth, I snuck my favourite foods into the cart: the two-pack of Ralph’s bulla cake or a spice bun, a pack of Oreos, and plenty of Ovaltine biscuits. When we approached the checkout, she engaged with the cashier, half paying attention to the items she’d unload to be paid for. I stood in silence, smirking as the items I cleverly chose were bagged, but of course there were casualties. She realized she didn’t actually pick up four packs of biscuits and then put them all, save for one, away, or she’d wonder what other items were unknowingly packed and go through each of them individually.

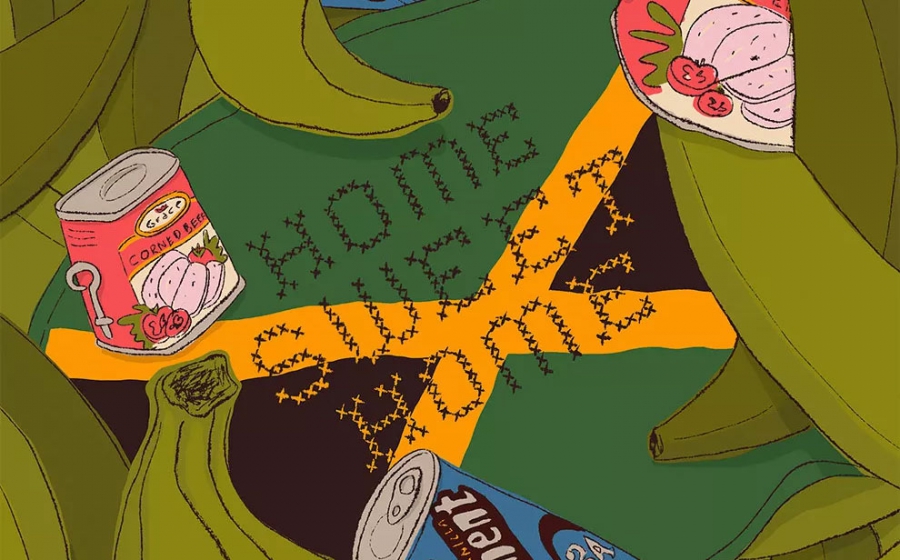

In my first year as a university student, independence looked like running wallet-first toward all the items I was forbidden to have in the past. However, in due time, the allure of an unregulated grocery list wore off. After a month, I found myself scaling down, drastically purchasing food in smaller quantities, all of which were unhealthy and easy to prepare: pizza pockets, TV dinners, and takeout. But three items were always around no matter what: plantain, Nutrament, and canned corned beef (affectionately known as "cornbeef" or "bully beef," depending on which Jamaican you ask).

My childhood memories of how my family engaged and stay connected with our culture are often wrapped up in memories about food. As a first-generation child of the Jamaican diaspora, I gleefully watched my grandma prepare Sunday dinner which would include a meal drawn from her personal inventory of sacred recipes from back home: stew peas, rice and peas, oxtail, and potato pudding. Still on the high of the Sunday sermon, she would come home and change into her house clothes and ask us to do the same because, of course, we smelled like “outside.” My cousins and I would watch whatever movie would be playing on YTV while our grandma prepared our food. No meal was rushed. She moved with purpose around the kitchen and even though barely any of the spices were labelled, she knew exactly which ones to use. These select dishes were the results of muscle memory that afforded her to replicate and rival dishes that she made while in Jamaica. A few hours later, she set the table for us and we’d devour the food in a fraction of the time it took her to make it. “Unu nah guh slow down?” she would ask, half laughing that this scene played out almost every week.

Between my mother's and grandmother’s house, there was an endless supply of plantains, Nutrament, and cornbeef. I can’t remember a time where I didn’t see one or all three of them stocked in either of their pantries. Neither my mom or grandmother explicitly said that these items were staple items that could be found in a Jamaican home but I found myself doing the same thing: picking up my plantain from the produce section and then heading down to the “international food” aisle to grab a tin of Grace Corned Beef and vanilla-flavoured Nutrament.

Corned beef isn’t particularly healthy, as it’s super high in sodium and fat, but it was affordable — although not so much now — and one can could be stretched among at least three people. I imagine that it would have been an ideal, easy, and cost-efficient way to feed yourself and two children in the ’70s, as was the case for my grandma who newly immigrated to Toronto. From my grandmother’s hands, I enjoyed bully beef on a plate of white rice, with fried dumplings, or alongside steamed cabbage, and from my mother’s, it made for a quick lunch sandwiched between two slices of hardo bread. As a student living on the margins, these were meals that were both easy to prepare and within my means, but I had always thought about whether our preference toward it was exclusive to my family or was a statement of something much larger.

Cork, Ireland, had been manufacturing and exporting corned beef during the 1600s right until 1825. The corned beef was sent in cans to feed an international demand, which proved to be useful for the British Navy, who sustained themselves on this cured meat throughout the Napoleonic Wars, and to overseas colonial powers, much like the one that existed in pre-independent Jamaica, who needed cheap food to feed slaves. Cabbage and sliced corned beef is still considered a traditionally Irish(-ish) dish, which is a whole other story, but in our household, it was served hashed and seasoned with spices, tomatoes, green peppers, and scallions.

I vividly remember laughing with my friends, most of whom were first-generation children as well, about the items that were always in our grandparents’ homes.

Other staples of my childhood diet would come to haunt me. One day I came home to the smell of something expiring and saw a black plantain that I had intentions to fry from earlier in the week. I shook my head, internalizing what would have been a chide from my grandmother about how wasteful I was being. “Sharine,” she would say, “yuh know mi coulda eat dis? You should not waste food!” If there had been any food that brought me comfort, it was plantain. It was all a matter of timing, figuring out when was the perfect time to eat it. I liked yellow plantains speckled with dark brown spots and lines, which was the stage it got to right before turning all black. That was when it was its sweetest. I craved it regularly, like when I was studying or on Friday evenings as a prelude to the weekend, but mainly to remind me of all the times I had shared plantain with my family.

Plantain itself is native to Southeast Asia but was brought over to the Caribbean when Europeans arrived. It is considered to be a staple because of its versatility — similarly to the banana — and can be baked, boiled, fried, or even turned into chips.

My mom used to get mad at my proclivity toward yellow plantain and instead opted for the green. She enjoyed her plantain a little firmer, starchier, and would sprinkle sea salt when it was done as an added touch. In my eyes, plantain was plantain was plantain. It wasn’t until I started grocery shopping on my own did I realize there was a difference between the two.

I had done this routine before of overpurchasing plantain and throwing it out but — even when I knew that I wasn’t going to eat it before it spoiled — I felt like it was necessary to have. The presence of these items made me feel closer to both my homes — my mom and grandma and the country of my heritage — and I often wondered if that was the same reason they had existed in my own family’s households.

I vividly remember laughing with my friends, most of whom were first-generation children as well, about the items that were always in our grandparents’ homes. Outside from the Lord’s Prayer that was pinned on a wall at least a foot away from the entrance, we agreed that meal supplement–adjacent drinks were always readily available: Nutrament, Milo, Supligen, Ensure, Ovaltine, and Horlicks being among the most popular. Nutrament, Ensure, and Supligen were drinks that I always had on hand because between school and work, I had very little time to prepare meals. I loved these kinds the best, as opposed to Milo, Ovaltine, and Horlicks, because it was a smooth drink, like a milkshake, and I never quite got down the technique to make a lump-free drink for the others.

With my grandma, I drank Nutrament during Sunday dinners. She prepared a specialty beverage of hers mixed with Tiger Malt, a nonalcoholic, carbonated molasses beverage from Barbados that we could only have after we cleared our entire plate.

I’m not sure why or how drinks of this variety became and still are so popular. I chalk it up to the communities built behind these products and how accessible they are. In the times that I’ve frequented Jamaica, Supligen is sold by nearly every street vendor for as low as 100 Jamaican dollars (about one Canadian dollar). People commuting from work, students commuting from school, or anyone wanting a quick pick-me-up can get one on the go. More recently, the reigning king of the dancehall, Vybz Kartel, liberated "Mhm Hm" late last year, which outlined a recipe that involved blending oats, Supligen, nuts, and nutmeg. So the dancehall king spoke, so the people listened, and the sales of both Supligen and the mixture spiked up.

Plantain, Nutrament, and cornbeef were my choice comfort foods. It was important for me to have them on hand during my first few years living alone because I was going through a transitional period. Their mere existence in my pantry was enough to remind me that even rented houses could somewhat feel like home, and I took solace in that. I needed them so I could cultivate a sense of home and connection, which I felt was lost amid extracurricular activities, work, and assignments.

After years of living alone, I’ve become a much wiser shopper. My diet’s changed and lately it doesn’t seem that there’s much room for Nutrament and cornbeef anymore, though I still feel closely connected to and with plantain. I’ve found different ways to stay connected that mostly involve travelling and finally learning how to recreate some of my grandma’s famous dishes (though they’ll never be as good) but those foods still have a special place in my heart. When I see a can of Nutrament at my grandmother’s house, I know she’s about to make her special drink and though cornbeef is a rarity in all of our pantries, I don’t think I’d ever deny how tasty it is.

I frequently dote on what my grocery shopping experience would be like as a parent and if I were to have a child, what foods would be the backdrop to their memories of family and home. I don’t know what foods those will be but I won’t deny the often unspoken power they have in shaping identities, as they have mine. ?

Sharine Taylor is a Toronto-based artist and writer.

Contact Sharine Taylor at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..